NADEZHDA LAMANOVA

Глава из книги Т.К. Стриженовой

Nadezhda Lamanova holds a special place among the clothes designers of the 1920s, not only because she was the first professional clothing designer of her time, but also because of the immense contribution she made to the development of theoretical principles of Soviet design, and the creation of the first examples of contemporary clothing.

Her professional life began in 1885, when, at the age of 24, she opened her own workshop. Her talent soon made itself known, and when she opened a business in Moscow she enjoyed great popularity and a wide clientele among intellectuals, writers, actors, and artists. What attracted everyone was not only Lamanova’s exceptional talent and her professional skill, but a genuine artistic trustworthiness. Her keen eye, subtle taste, and thorough knowledge of costume helped her to immediately grasp the peculiarities of a person’s character and figure and to decide unerringly on the most suitable cut and style of dress.

Annual trips to Paris, the fashion center of that time, refined her knowledge. She collaborated with France’s most celebrated designer, Paul Poiret, who instantly recognized the Russian artist’s extraordinary talent and repeatedly asked her to move to Paris to work with him. Lamanova, however, refused.

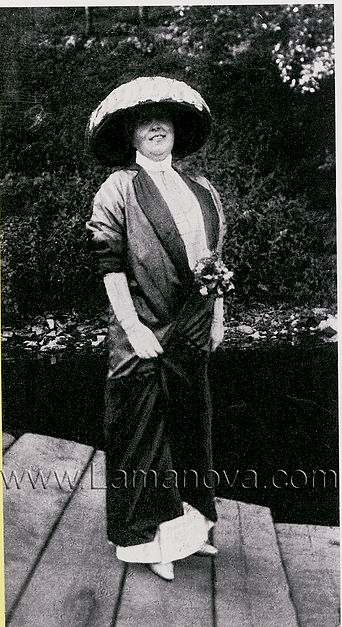

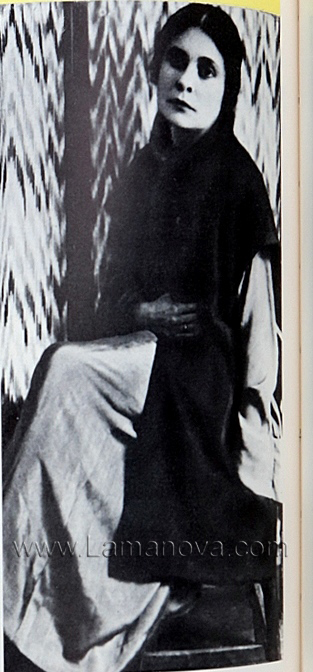

Nadezhda Lamanova. 1910. A dress-designer for the royal court. Lamanova kept designing after the revolution of October 1917 experiencing in her declining years a resurgence of her creative powers. She dedicated herself to the creation of mass clothes for the people of the «marvelous new world».

Надежда Ламанова. 1910 год. Дизайнер одежды для королевского двора. Ламанова продолжала конструировать после революции октября 1917 года, испытывая в ее преклонном возрасте возрождение творческих способностей. Она посвятила себя созданию массовой одежды для людей «чудесного нового мира».

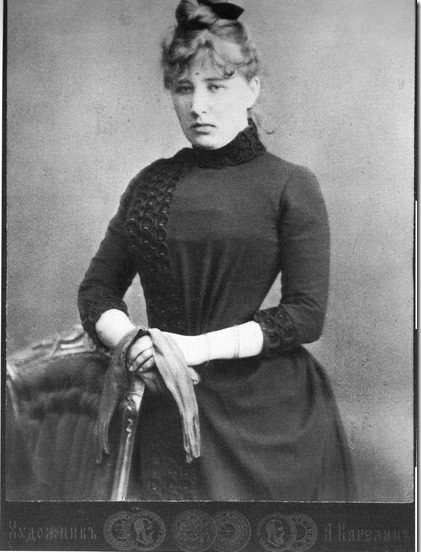

Portrait of young Nadezhda Lamanova. 1880s

Portrait of young Nadezhda Lamanova. 1880sAutobiography

I was born on 14 December 1861. I attended the well-known dressmaking school of O.A. Suvorova (1883). And in 1884-1885 worked for hire as a designer at Voitkevich’s dressmaking establishment. From 1885 to 1917 I had a dressmaking establishment of my own.

I began working for the Moscow Art Theater in 1901. And made costumes for the play In Dreams by V.I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, and The Cherry Orchard. In 1918 I joined the Art Workers’ Union and again worked for the Art Theater.

From 1919, I was head of the State Training and Manufacturing Workshop of Costume at the Art Industry Department of the People’s Commissariat of Public Education of the RSFSR, under the Central Science Board, and simultaneously an artistic modelling instructor at the Igla (Needle) Section of the Moscow Public Education Department. During that period I organized the exhibitions.

In 1921 I began working at the Vakhtangov Theater, where I have been working for sixteen years. I have constructed costumes for the following plays: Turandot (the costumes are altered every one or two years), Zoika’s Flat, The Daughter of a Russian Actor, On Blood, Marion de Lorm, Kable und Liebe, Egor Bulychev, Dostigaev and Others, The Envy, Hamlet, The Human Comedy, Florisdorf, Much Ado About Nothing, and Guilty Though Guiltless.

I also work at Griboedov Stidio. In 1924, I organized a handicraft workshop and made models ordered by state institutions and theaters: Inga, the Theater of the Revolution; Aelita, for the cinema; and the play The Inspector General, MOSPS.

ln 1925, at the request of the Kustexport Corporation, i organized and executed models for the Paris Exhibition, receiving First Prize.

In 1926 I made designs for the peoples of the North, commissioned by Vsekopromsoiuz. In 1928, I designed tor the exhibition of Arts and Handicrafts of the State Academy of Artistic Sciences. In 1926, I made, after Golovin's sketches, costumes for the play The Marriage of Figaro at the Art Theater.

In 1929, I fulfilled an order for designs to be exported. In 1930, I made fur models for the exhibition in Leipzig, commissioned by All-Union Western Chamber of Commerce.

ln 1929, on order from Vsekopromsoiuz l executed designs for the exhibition in New York, and a year later worked as chief of the design workshop of the Furs Combine.

In 1932, I took employment at the Art Theater as a consultant and constructor.

In cinematography, l made the costumes for the films: The Generation of Winners, The Circus (Lenfilm) (In fact Mosfilm), The Inspector General (Ukrfilm), and Alexandr Nevsky.

Moscow Art Academic Theater оf the USSR

13 February 1933 (Perhaps a mistake, more correctly 1937).

Arkhiv MKhAT. d. 5085/1-6 Copy

On the eve of the October Revolution, when Lamanova was 46 years old, her firm claimed the uppermost aristocratic circles as its clients, and its signboard included the inscription «Provider to the Court of His Imperial Majesty».

Perhaps some artists in their declining years, who had earned official and public recognition and a firm position in society, might not have survived the spiritual upheaval of the revolution and its intrusion into their artistic lives. Lamanova, however, unhesitatingly embraced the revolution, and approved its ideals. She explained her position:

«The revolution has changed my property status, but it has not changed my fundamental ideas; in fact it has given me the opportunity to put them into practice on an incomparably larger scale». (Notes of N. Lamanova. Manuscript. Archives of T. Strizhenova.)

Her position can be understood through her biography. Nadezhda Lamanova was the child of a serviceman of modest means, became an orphan while very young and had to support her younger sister, combining work with study. In the years of the First World War, when Lamanova was already solidly established, she readily allowed her estate to be used as a military hospital.

Kindness, humanitarianism, and simplicity were her principal characteristics. She parted with her firm and the privileges of her position without complaint. She also underwent many difficult experiences: she spent the first years after the Revolution in the Butyrskaia prison, indicted as a «bourgeoise», and was later released through the intercession of the writer Maxim Gorky, then head of the state publishing house. In the 1930s she was disfranchised, and she and her friends had to argue tirelessly to prove how much she had done for the Soviet system.

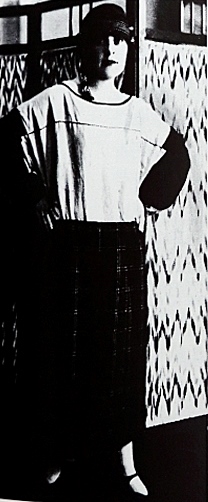

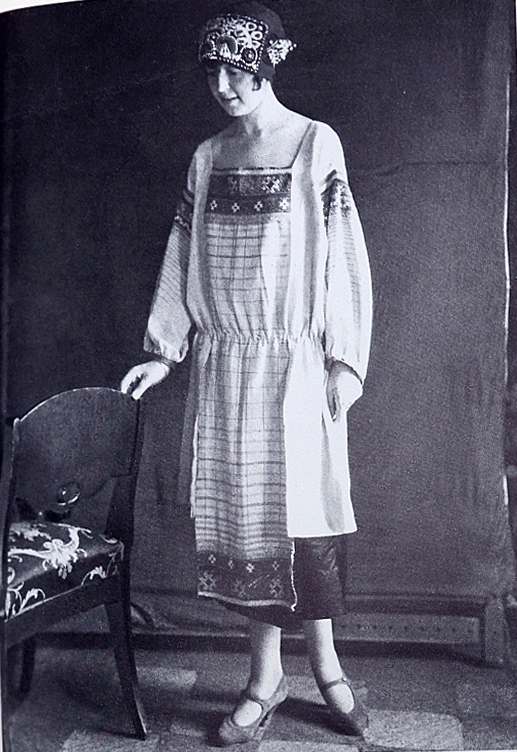

Lilia Brik and Alexandra Khokhlova, a silent film star, modelling Lamanova’s designs in 1923. Cloche hats were fashionable at that time. Lamanova and her younger sister Maria ornamented these hats with old embroidery. One of Lamanova’s favorite clients and models was Alexandra Khokhlova. The designer emphasized the eccentricity at her model’s manners and facial expression with flashy garments of striped fabrics. The dynamic rhythm of the stripes in the blouse contrast with the quiet lines of a narrow black skirt.

Лиля Брик и Александра Хохлова, звезда немого кино, демонстрировали модели Ламановой в 1923 году. В то время были модны шляпы. Ламанова и ее младшая сестра Мария украшали эти шляпы старой вышивкой. Одной из любимых клиенток и моделей Ламановой была Александра Хохлова. Дизайнер подчеркивала эксцентричность манер и выражения лица своей модели роскошной одеждой из полосатой ткани. Динамический ритм полос в блузке контрастирует со спокойными линиями узкой черной юбки.

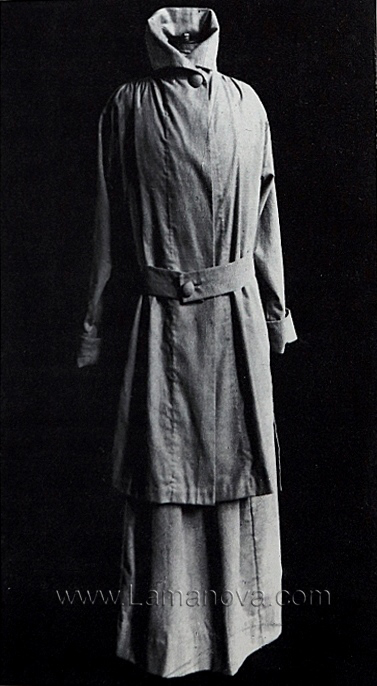

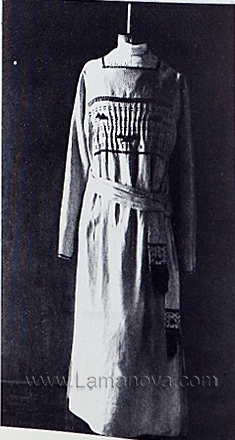

A summer coat ornamented with folk embroidery designed by Lamanova. 1923.

Летнее пальто украшено народной вышивкой, разработанной Ламановой. 1923.

Lamanova's designs of 1923-1925, a silk dress trimmed with fur. Sometimes an almost uncut shawl with a patterned border became the front of a costume. Lamanova had folk-embroidered towels inserted in the form of an apron into a chemise-type dress.

Дизайн Ламановой в 1923-1925 гг., шелковое платье, отделанное мехом. Иногда перед костюма состоял из почти неразрезанного платка с узорчатой рамкой. У Ламановой были вышитые народные полотенца, вставленные в платье-рубашку в форме фартука.

No humiliation seemed to crush the will of this remarkable woman.

Lamanova’s creative biography is also very complicated. Prior to the revolution, she worked in the fashionable «moderne» style, her productions following the trends in Paris garments. Several such dresses are in Leningrad’s Hermitage Museum. Intended for the Russian aristocracy, they are characterized by an intricate and labor-intensive execution, and also by the use of expensive foreign fabrics and decoration. Although different from each other in cut, shape and decorative details, they are similar in the elegance of the silhouette, perfect proportion, and clever choice of the texture and color - in a word, they possess the harmony that distinguishes a work of art from ordinary tailoring.

The gift of Nadezhda Lamanova was not unlike a sculptor’s talent - she could envision how each fabric would look on a person and what shape suited the figure. She herself did not make the garment, but did «the pinning» of the material on a human figure, delineating the contours of the cut and of the decoration. Her method of dress design could be called «sculpting in fabric».

Lamanova often told her students that the most important aspect of their work was finding the shape of costume that was appropriate to the person, not inventing a «style» or fashionable attributes that allegedly determine the aesthetic merits of clothes. She believed that costume was inseparable from the individual. Therefore the artist banished the words «style» and «fashion» from the designers’ vocabulary, replacing them with the notions of «shape» and «design». She was the first to draw a line between the tasks of costume designer and seamstress, emphasizing their specificity:

«l create designs of women’s clothes, I do the pinning and determine the shape and decoration, but I do not perform the technical part of the work. I cannot do this work as an architect cannot build a house, or as a blacksmith cannot work without a striker». (Notes of N. Lamanova. Manuscript. Archives of T. Strizhenova.)

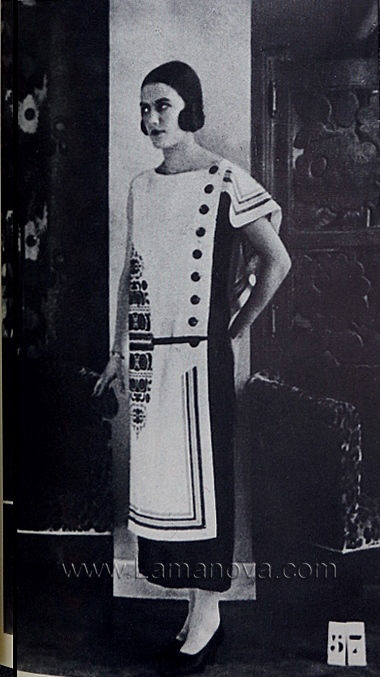

Handmade embroidery formed an integral part ot the construction of a garment. With her fine sense of form Lamanova could combine the detail of folk embroidery with an asymmetrical row of buttons, an item which could then be worn over the dress. 1923

Ручная вышивка является неотъемлемой частью конструкции предмета одежды. С ее прекрасным чувством формы, Ламанова могла объединить детали народной вышивки с асимметричным рядом кнопок, затем этот элемент костюма можно было носить поверх платья. 1923

Примечание к публикации: модель принадлежит авторству Поля Пуаре. Исследование идентификации опубликовано в разделе «Казусы и мифы».

Lamanova did not make sketches of her designs, because she could not draw; they are known from photographs of the actual models housed in her personal archives. (These archives were kindly presented to me by the artist’s younger sister Maria Petrovna and her niece Nadezhda Krakht. Reminiscences of her relatives, students, and acquaintances, almost all of whom are now dead, are also important for understanding Lamanova’s art. I was particularly helped in the preparation of this book by the now deceased F. Gorelenkova and N. Makarova, two of Nadezhda Lamanova’s students.)

Whereas in private life Nadezhda Lamanova was exceptionally kind, in her work she was severe and demanding, totally confident that her point of view was correct. She rarely took into account the clients' wishes and was firm in her choice of design. Fitting was for her a truly creative act: she pondered over the style and the system of cutting, considered the distribution of folds of the textile on the figure, bearing in mind all the particularities of construction in relation to the shape of the body. She paid attention, moreover, not only to the lines of the «front» but also to the figure as a plastic volume, always checking to see how the dress changed when it moved.

As the actors who knew Nadezhda Lamanova recalled, it was at once difficult and easy to work with her. It was difficult because of the way she tenaciously decided on the style of the costume, disregarding their wishes. She made long and repeated fittings, tiring the client, until she was sure that everything was perfect. On the other hand it was easy, because she was absolutely reliable: the result of the work was always an irreproachably made dress.

With the Revolution a new era began in Lamanova's life: her talent and immense practical experience allowed her at last to engage in largescale and diverse activities. Taking the lead in restructuring garment production, the artist experienced in her later years a rejuvenation of her creative powers.

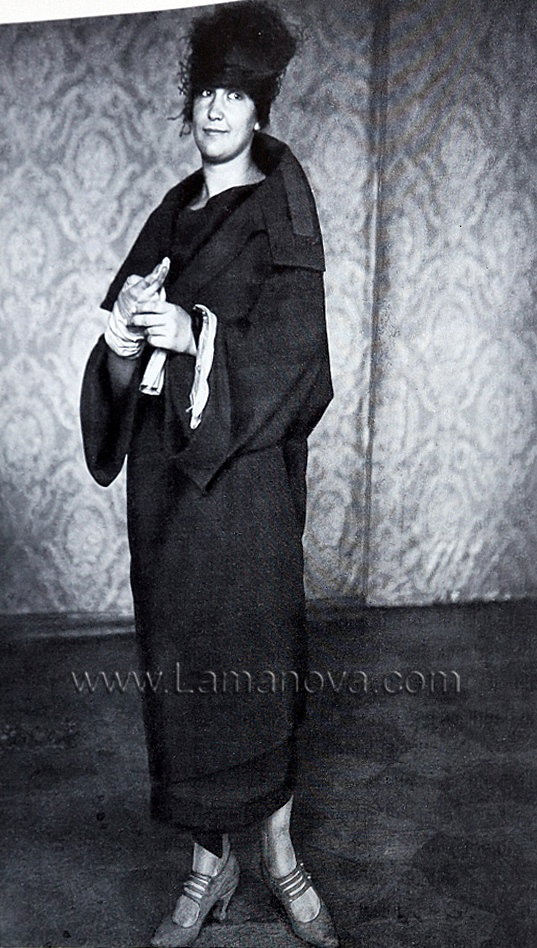

Lilia Brik modelling Lamanova's dress made ol homespun textiles. 1923

The same dress reconstructed in 1985 by Elena Khudiakova. Khudiakova, a well-known designer in her own right, models the dress.

Лилия Брик демонстрирует модель Ламановой из домотканого текстиля. 1923

Это же платье было реконструировано в 1985 году Еленой Худяковой. Худякова, известный дизайнер, в своих собственных моделях.

She joined the work of Soviet institutions with enthusiasm, showing outstanding organization abilities. She created the Workshops of Contemporary Dress at the Narkompros industrial art subsection, became a member of the dress section of the State Academy of Artistic Sciences and collaborated on the Journals Atelier and Krasnaia niva, both as the author of articles and as clothing designer. The concept of the purpose of art expressed in the romantic revolutionary slogans of those turbulent days, and the desire to integrate art into all aspects of daily life and industry, stuck a responsive chord in the designer.

Despite her time-consuming administrative and organizational work, she continued to design clothes. She wrote in 1922: «My work consists of creating designs of modern women’s clothes, and l have always tried to use simplicity and logic in my designs, proceeding usually from the specific characteristics of the fabric. . . .» (TsGALI, f. 941, op. 10, d.341, p.3).

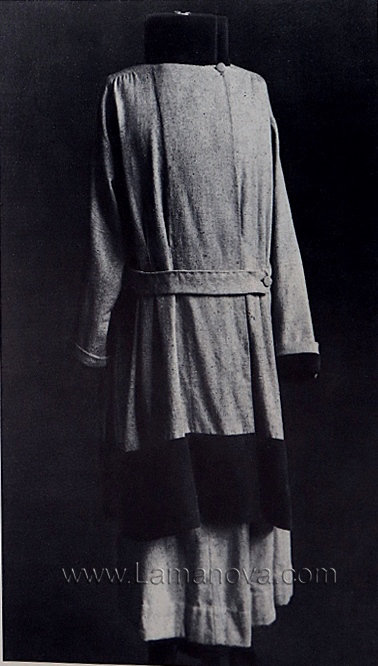

Lamanova's designs of 1923. Costumes made of unbleached linen and a coarse wool cloth typified textiles of the austere years.

Модели Ламановой 1923 года. Костюмы из небеленого льна и грубой шерстяной ткани были типичным текстилем тех суровых лет.

In the years following the revolution, Lamanova had a clear conception of the trends in Soviet costume: clothes for everyday wear and clothes featuring folk motifs. For models, Lamanova most often used Alexandra Khokhlova, a silent-film actress, her student Nadezhda Makarova, and Lilia Brik. Sometimes the amateur photographs taken of these clothes are joined to a narrow swatch of the textile from which the garment was made. They are plain, poorly colored and, as a rule, non-patterned textiles: brown Holland, flannelette and calico. With them the artist produced simple dresses of elongated proportions, mostly of the chemise type. For ornament, use was sometimes made of decorative colored insets, or the alternating of dark stripes on a white ground, which somewhat resembled the constructivist’s geometric drawings; often a subtle pattern of the fabric was the basis for the decoration of the dress.

One feels that Lamanova deliberately, and on principle, tried to simplify the cut. In her explanatory note to the Workshops of Contemporary Dress, the artist pointed out that the new workshops could develop «methods for simplifying costume as a characteristic feature of worker’s garments in contrast to the garments of the bourgeoisie».(N. Lamanova’s personal archives). But that was not her only motive for simplicity.

Unpretentious clothes were certainly suited to the austere life of that time. What were needed were garments that were simple, comfortable, inexpensive and practical. The available materials - limp fabrics that could not keep their shape or, on the other hand, thick, coarse material (mostly soldiers’ cloth) - dictated the form the garment would take. No wonder Lamanova’s basic formula was: «Material determines the shape».

The amateur photographs in her archives allow us to follow the current of her artistic search. For instance, one can see three models of a coat very similar in cut: they have in common a straight silhouette, a stand-up collar and a wide belt.

But each model has its own solution, depending on its purpose. In the short coat of woolen cloth, stress is laid on the streamlined statuesque form, with its sections made conspicuous by raised stitching. Beside it is a model of the same coat made of canvas, a thinner material: it has tucks under the stand-up collar producing a picturesque play of rigid little pleats; the belt is clasped with a buckle wrapped with string; it has below, in the middle, a rectangular cut-out that gives the garment originality and performs a definite function-preventing creases when walking. In the third version of the coat (probably made of flannelette), proportions are altered: it is longer and considerably wider than the first two, hence the fabric falls in soft folds. The waist is tightly girdled with a wide sash. Lamanova thus demonstrated the possibilities of offering several versions from a single construction.

Lamanova’s designs of 1925. A coat. Lilia Brik in Lamanova's two-color costume. 1923.

Дизайн Ламановой 1925 год. Пальто.

Лиля Брик в двухцветном костюме Ламановой. 1923.

Lamanova’s archives contain one watercolor sketch, which depicts an unusual model of a dress in varying tones of blue. It is not signed, but, judging by the subtle color scheme and the sure and free stroke of the brush, the executor could have been Lamanova’s friend Alexandra Exter. This dress, too, is cut as a chemise, with a high neck, rather wide sleeves and a wide twice-wound sash of the same material linked with a decorative black buckle in a convex rectangle. Worn over the dress is a short jacket with sleeves shorter and wider than those of the dress.

This deceptively simple model is a masterpiece. This detail forms a second version of the attire. The modest, refined ornamental details include strips of grey, terra-cotta, and blue decorating the collar, cuffs and sash. It was to be made of a fabric like crepe satin and was therefore to serve as a «fancy» dress. It is likely, however, that the garment was never made. Lamanova also designed a large series of everyday dresses made from a single shape, an elongated rectangle. These simple garments acquired individuality because of the decorative appliqué in the form of broken geometric lines or of thin semicircles.

Lamanova exhibited much more freedom when designing dresses displaying folk motifs. Her treatment of these motifs was absolutely extemporaneous and always surprising. She would use pieces of genuine antique lace for the bottom of a dress with a modern picot edging, employ a genuine Russian towel for the front of the dress, and make the bodices from lace curtains richly embroidered in satin-stitch. This was not mere «appliqué», as in many such works of folk art, but the design of an integral construction as a plastic volume, a coordination of all its elements.

This side of Lamanova’s work was quite deliberate: she was well aware that she addressed amateur dressmakers, who, by using her methods, could improve their garments and individualize them with folk-embroidered towels, pillow-covers, crochet-work and other traditional household fabrics.

It was a garment of this genre that the artist sent to the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes held in Paris in 1925. The rectangular-shaped dress included a richly embroidered towel In its lower section; similar towels were used for the sides and the back. A narrow red braid edged the neckline and sleeves, harmonizing the whole. There was a modish little hat to match. This ensemble, simple but sensational, produced quite a stir among the sophisticated Paris public. Lamanova received the Grand Prix «for national originality combined with the modern fashion trend». In her article «The Russian Style», Lamanova wrote: «One of the interesting endeavors in the field of modern costume is the modification of the forms and character of folk costumes and their application to everyday clothing. The rationality of the folk costume, thanks to the age-old collective efforts of the people, can serve both as the ideological and the practical model for our urban clothes. The basic forms of folk costume are always wise. . . . It is by introducing specific colors and distributing them in rhythmic succession on a rationally made costume that we make the type of clothes that are in harmony with our contemporary life» (Krasnaia niva, 1923, no.30, p.32. Though the article is not signet, most people agree that it was very likely written by Lamanova. Moreover, a sample of a garment illustrating it closely resembles the skatches found in the artist’s personal archives and her article «On the Contemporary Costume», published in the journal Krasnaia niva (1927, no. 27, pp. 662-663))

Sometimes the designer incorporated seemingly discordant elements: in a fashionable «mantelet-dress», for example, she used a fragment of folk embroidery, strips of different color along the hemline and the cuffs, and a long row of large buttons asymmetrically placed along the side. The unusual mantelet began at the sleeves and formed part of a kerchief that hung in a triangle down the back. The mantelet could be worn over an everyday dress, transforming it into an original, fashionable ensemble.

The artist's favorite type of clothing was a woman’s suit comprising a dress, a skirt, and a jacket that she called a «caftan». These ensembles could highlight the quality of the fabric (when it was of good quality) and, of equal importance, allow the designer to compare and contrast the parts: a narrow straight skirt with a Ioose-fitting blouse, a straight long dress with extra-wide sleeves; sometimes a dress draped with asymmetrically placed pleats.

Lamanova's designs at 1923. A costume incorporating embroidered towels. Using available materials - a curtain or a coverlet – Lamanova constructed a fashionable garment in white tulle with a lace fringe. The ensemble consists of a long straight blouse, a straight skirt, a small hat and a belt ornamented with similar decorative elements.

Дизайн Ламановой 1923 год. Костюм с вышитыми полотенцами. Используя доступные материалы - занавес или покрывало - Ламанова построила модный предмет одежды в белом тюле с кружевной бахромой. Ансамбль состоит из длинной прямой блузки, прямой юбки, маленькой шляпы и пояса, украшенного подобными декоративными элементами.

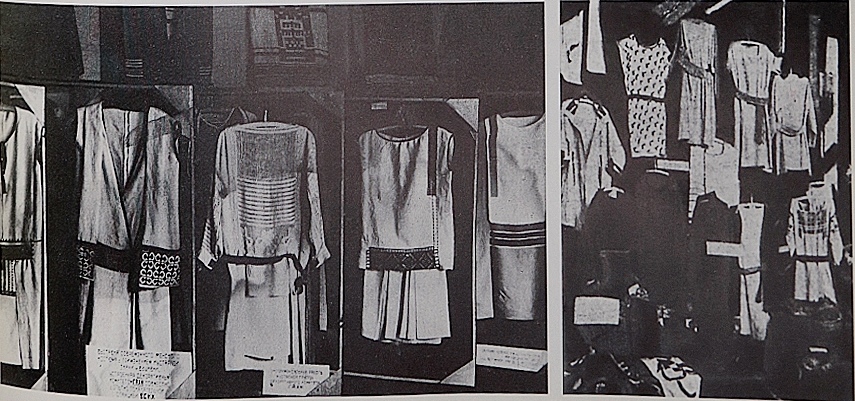

Lamanova's designs of 1923. Costumes trimmed with lace and emboidery.

Модели Ламановой 1923 года. Костюмы, обтянутые кружевами и вышивкой.

A Lamanova design from 1923. A dress decorated with braid.

Модель Ламановой 1923 год. Платье украшено тесьмой.

Lamanova believed that contrast in the design of models made them dynamic: «The absence of contrast and, consequently, of dynamism makes the silhouette dry, monotonous, and lifeless».

Both Lamanova’s theories and practice closely resembled constructivism in their functionalism and expediency. In the artist’s works, however, the image-bearing, emotional principle always predominates. Ornament and color were its vehicles. Lamanova’s theory on the laws of ornamentation of clothes is also very interesting, although not directly related to design for mass production. In her best works the artist displayed a sense of proportion in the nature and placement of the garment’s finishing touch, the ornament. Unprinted fabrics and the straight chemise-type silhouettes left large plain surfaces requiring decoration. Following folk principles of ornamentation, Lamanova distributed decorative elements in places dictated by the garment’s construction, such as the bodice, shoulders, cuffs, and hem. Most often she used genuine folk motifs - the borders of napkins or towels - but sometimes she herself made the ornament in a constructivist or modern style. The peculiarities and rhythm of the decoration harmonized with the overall outline, the specific cut, the texture and color of the fabric. Ornament in everyday costume became Lamanova’s preoccupation after 1924, when she was made head of the arts and crafts workshop that filled orders for Kustexport (Handicrafts Export) and other organizations for domestic and international exhibitions. The designer began to pay more attention to ethnicity in costume and decoration. Captivated by the decorative splendor of embroidery, she occasionally used it to excess, and these designs seemed less integrated than her more restrained models.

It is easy to see from her archives that all the works of Nadezhda Lamanova, however varied they might seem, have in common «a single foundation», the rectangle. Taking into consideration the properties and possibilities of the fabrics that were available, the artist «translated» the rectangle into countless clothing designs. The starting point for most dressmakers was fashion; they disregarded the properties of the material, and even tried to disguise them with elaborate decorative design. Neither the individual characteristics nor even the figure of the wearer had much bearing on the design. No wonder the corset lasted so long (in Europe it was still being worn in the 1920s). This artificial frame altered and often distorted the figure, subordinating it to the construction of the dress.

Clothes by Nadezhda Lamanova, Alexandra Exter, and Evgenia Pribylskaia shown at the exhibition of modern woman’s costume in Moscow in 1923. On display were mostly richly ornamented dresses made of homespun fabrics with embroidery based on the principles of folk costume.

Модели Надежды Ламановой, Александры Экстер и Евгении Прибыльской показаны на выставке современного женского костюма в Москве в 1923 году. На выставке были в основном богато украшенные платья из домотканых тканей с вышивкой, основанные на принципах народного костюма.

Lamanova's projects to reach fruition, and she was compelled to remain within the limits of laboratory experiments.

Frustrated with the lack of industrial capacity to provide the population with decent modern clothing,Lamanova tried to enlist still another category of the population. With her closest friend Vera Mukhina, she published in 1925 the album Iskusstvo v bytu (Art in Everyday Life), in wich they addressed women who made their own dresses, offering them their designs of everyday clothes, which were simple In cut and easy to understand even for beginners. Each drawing of a model was accompanied by its pattern and a detailed description of appropriate fabrics, and even color suggestions. In geometrizing their drawings, the authors simplified their patterns to the extreme, while subscribing to the tenets of the well-known constructivists, who divided all drawings into geometric planes. The editorial in the album said that the condition of the country at the time «does not provide sufficient material prerequisites for a radical transformation of our entire culture, which will come with the final triumph of socialism. . . . The new forms, the culture of dressing, the rational and well - arranged everyday life . . . can be achieved without the aid of professionals, but with the creative efforts of the working family, of the school or club collective» (Iskusstvo v bytu, Moscow, 1925).

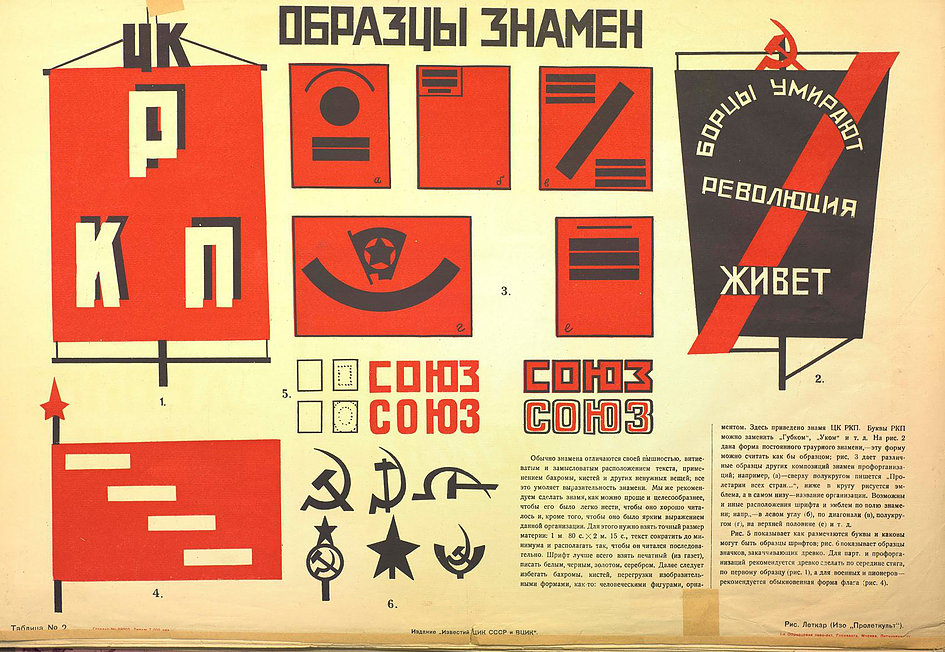

The distinguishing feature of the designs is their simplicity and functionality of cut. The authors addressed their journal to self-taught dressmakers. The title page says that the album contains 36 tables within the sections Toys, Clothes, Village Library and Reading-Room, Club and Theater. Homespun linen could be used to make a Young Pioneer uniform for boys and girls. The album includes samples of banners, which are designed in a spirit of constructivism, without the «fringe, tassels and other unnecessary details». The black banner is a «banner of permanent mourning». It has the inscription: «Fighters die, the Revolution lives on. «Lamanova advises using durable linen fabrics to make a comfortable sports outfit including a blouse and a skin or trousers. Patterns and explanations are given next to the drawings.

Отличительной особенностью конструкций является их простота и функциональность кроя. Авторы обратились в своем журнале к портнихам самоучкам. На титульном листе говорится, что альбом содержит 36 таблиц в разделах «Игрушки», «Одежда», «Деревенская библиотека» и «Читальный зал», «Клуб и театр». Льняное полотно можно использовать для создания детской пионерской формы для мальчиков и девочек. Альбом включает в себя образцы баннеров, которые разработаны в духе конструктивизма, без «бахромы, кисточек и других ненужных деталей». Черный баннер - «знамя постоянного траура». В нем есть надпись: «Борцы умирают, Революция живет». Ламанова советует использовать прочные льняные ткани для создания комфортного спортивного снаряжения, включая блузку и кожу или брюки. Шаблоны и пояснения приведены рядом с чертежами.

Lamanova was continually aware - whether she designed for the industry or for a small workshop - of the possibility of her patterns being used at home. Her models encouraged amateur dressmakers to seek simple, expedient forms, and taught them a judicious use of folk themes.

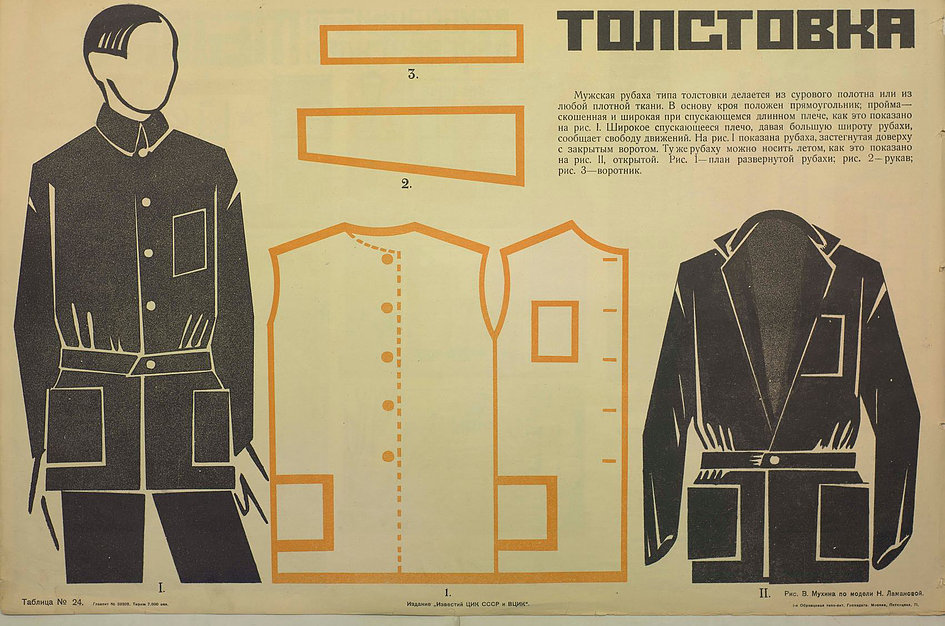

The album displayed summer and winter dresses, jackets and coats, sports clothes and a «Young Pioneer» uniform. There were even theater costumes by Vladimir Akhmetiev, including the costume of a female worker, which could be easily transformed into the costume of a «bourgeois». Both the cut and decorative elements of the designs emphasized their distinctive national character. One of the most interesting samples was a dress made of kerchiefs. The cashmere fabric and the small red and green flowers printed on the kerchief gave the native-looking costume a fashionable appeal. Also attractive was a costume in three versions: to be worn in the street, at home, and at work. Its transformations depended on minimal alterations. A straight, impressive-looking coat was cut, with utmost simplicity, from a length of army cloth. lt is described in the album: «The coat (the width of the fabric being about two meters) is of one piece. Only the arm-hole is cut out. The sleeve has only one seam: the projecting piece in the pattern, when folded in two, forms a gusset for free arm movement. The collar represents half a square; its long diagonal side is sewn beneath the neck following the dotted line. After being sewn on, the remaining ends of the collar are buttoned on the shoulder line. lf the cloth is narrower, the sides have seams, with the form of the rectangle remaining» (Iskusstvo v bytu. Moscow, 1925 (from the description of the model)). The garments the album include a sort of prozodezhda: a Tolstoy-style man’s shirt, a blouse and a skirt (designer V. Akhmetiev); a sports outfit consisting of a blouse and culottes; and headgear (designer V. Mukhina). The album also contains easy-to-execute building projects: a village library and reading-room, a village theater, a bookcase combined with a show-case, and much more. Artists from different fields tried to assist in creating, with minimal resources, a new environment appropriate to the new life. The design of the album, by Vera Mukhina, was well conceived and splendidly executed down to the smallest detail.

Pages from the album lskusslvo v bytu, 1925. Designs by N. Lamanova. Lamanova suggests using woolen or cotton kerchiefs to make a house dress. The cut is based on a square. Lamanova explains how the pattern should be altered tor a more slender figure. A summer dress can be made of brown Holland cloth. The pattern shows two versions of the design, with and without sleeves.The dress is trimmed with a fabric dyed at home in a contrasting color.

Страницы из альбома Искусство в быту, 1925. Проекты Н. Ламановой. Ламанова предлагает использовать шерстяные или хлопковые косынки для изготовления домашнего платья. Разрез основан на квадрате. Ламанова объясняет, как шаблон должен быть изменен для более стройной фигуры. Летнее платье можно изготовить из холста. Шаблон показывает две версии дизайна, с рукавами и без них. Платье обрезается тканью, окрашенной дома контрастным цветом.

Pages from the album Iskusstvo v bytu. 1925 Designs by Lamanova, including the so-called Tolstoy-style shirt and a coat made of army cloth. Loose linen blouses were very popular among Russian intellectuals who imitated Leo Tolstoy’s style of dress. While retaining the name oi the shirt, Lamanova altered the cut. In her interpretation the shirt is close to the constructivists‘ prozodezhda and barely resembles the loose half-peasant shirts with a yoke. The out of the coat is quite original, with no seams at the sides and with a triangular collar.

Страницы из альбома Искусство в быту. 1925 г. Дизайны Ламановой, в том числе так называемая рубашка в стиле Толстого и пальто из армейской ткани. Свободные льняные блузы были очень популярны среди российской интеллигенции, подражавшей стилю одежды Льва Толстого. Сохраняя название рубашки, Ламанова изменила разрез. В ее толковании рубашка близка к конструктивизму и прозодежде и почти не похожа на свободные полу-крестьянские рубашки с ярмо. И пальто довольно оригинально, без швов по бокам и с треугольным воротником.

The combination of original drawings and plans, handsome typography and skillful use of color made the volume an illustrious example of fine art in design.

Lamanova worked on everyday costume design approximately until the mid-1920s, and for some time after that was occupied with the design of models from homespun textiles. Her contribution to the theory of garment design was substantial. She wrote the program for the Workshops of Contemporary Dress and the curricula of the first Soviet schools for clothing design, made reports at conferences and wrote a number of articles for the journal Krasnaia niva. It appears that the artist was preparing to publish a book summing up her extensive experience. She wrote in 1922 in her autobiography: «I have started to organize the data that I have worked out and put to practical use during my career» (GAKhN, f.941, op. 10, d. 341. Autobiography of N. Lamanova).

Even if Lamanova could not draw, she certainly had a writer’s gift. Her many articles impress not only by their splendid mastery of the intricate problems of costume, but also by their logic and compositional harmony and their original turn of phrase. In her article «The Russian Style», Lamanova raised the question of the new Soviet costume and tradition. (Krasnaia niva, 1923, no.30. p.32). Her well-known article «On Contemporary Costume» (Krasnaia niva, 1924, no.27. p.662-663) contains a classification of the new forms of clothes into everyday and holiday attire, shows their kinship to the principles of folk costume, and analyzes in detail the necessity of constructing a costume to suit the individual figure.

Lamanova’s writings include another article prepared for the press, «On the Rationality of Costume». It apparently served as the basis for the 1928 theoretical program. It was here that the artist formulated the «principal factors of costume», and gave her famous maxim, «the purpose for which the costume is created, for whom and from what», which she advansed as the creed of clothing designers.

Pages from the album IskussTvo v bytu, 1925. Designs by Lamanova. A caftan made of two towels from the Vladimir region and a costume for wear on the street and at work. The 1920s saw an acute shortage of textiles, which was why Lamanova designed clothes to be made of kerchiefs, army cloth (there were no other woollens) and embroidered towels. Necessity is, indeed, the mother of invention.

Страницы из альбома Искусство в быту, 1925. Проекты Ламановой. Кафтан из двух полотенец из Владимирской области и костюм для улицы и для работы. В 1920-е годы остро ощущался дефицит текстиля, поэтому Ламанова разработала одежду из платков, армейской ткани (другой шерсти не было) и вышитых полотенец. Необходимость - это действительно мать изобретения.

Lamanova’s theory was made public in full in 1928 and was presented at the exhibition of Handmade Textiles and Embroidery in Woman’s Contemporary Costume. The main items of the program were the costume’s purpose, its material, the figure of its wearer, and its form:

The costume’s purpose determines the material.

The figure, in turn, determines the material and color.

The form determines the material, the ornament, and the rhythm that coordinates these elements.

Ornament is used to integrate the material and the color.

Ornament is used to construct both the form and the weight.

Ornament divides the plane both artistically and constructively.

The form of the rectangle is determined by the material.

Material should be used sparingly, with little waste in construction. The form should permit free movement.

The material determines the form. (From T. Armand, Ornamentacia tkani, Moscow, Leningrad, Akademia, 1931, p.103).

These brief theses, which today might seem self-evident, caused a revolution in the art of dress. They created the foundation for a vast branch of decorative art which was in keeping with the nature of the new life, and was also its product. The principles of Lamanova’s theory can still be applied today, not only in costume design, but in other decorative arts.

Pages trom the album lskusstvo v bytu. 1925 A theatrical costume by the artist: Vladimir Akhmetiev. The explanatory notes show how he costumes - «working-class» and «bourgeois» - can be made from one pattern. Headgear alters V. Mukhina's sketches. While helping Lamanova to sketch her ideas, Mukhina designed clothes independently as well. Her headgear balances between the proletarian kerchief and hats of the Art Deco style.

Страницы из альбома Искусство в быту. 1925 Художник-постановщик: Владимир Ахметьев. Пояснительные примечания показывают, как его костюмы - «рабочий класс» и «буржуазный» - могут быть изготовлены по одному образцу. Эскизы головных уборов В. Мухина. Помогая Ламановой набросать свои идеи, Мухина самостоятельно разрабатывала одежду. Ее головные уборы балансируют между пролетарским платочком и шляпами стиля ар-деко.

Another important sphere of the remarkable artist’s activities was her work for theater and cinema. Lamanova was employed by the Moscow Art Theater for forty years, from 1901 to 1941, the year of her death. She created a multitude of costumes, for foreign classics as well as for plays by Soviet authors. The artist’s gift in this field was described by Stanislavsky in his letter to Alexander Golovin, the designer of scenery and costumes for the 1926 performance at the Art Theater of Beaumarchais’s comedy, «The Marriage of Figaro»: «We attempted having costumes made in the rough by ordinary tailors and dressmakers. The attempt proved beyond doubt that these people will not be able to convey the enormity of your talent. Nothing else was left to us but to apply to the person whom we consider to be the only one in Moscow artistically sensitive enough to materialize your sketches. This person is Lamanova. Perhaps you think that she is just another dressmaker who makes contemporary costume fashionable, but in fact Lamanova is a great artist, who, when she saw your sketches, responded with a true artistic ardor. For each costume she will be seeking with her own hands not hackneyed nor trite but highly individual methods of tailoring» (K. Stanislavsky. Sobranie sochinenii, vol. 8, Moscow, Iskusstvo Publishers, 1961, pp. 136-137). In the 1920s, Nadezhda Lamanova also became involved with the Evgeni Vakhtangov Theater, the Revolution Theater, and the Red Army Theater. In her work for the cinema, she made the costumes for the films Aelita (directed by Yakov Protazanov), Ivan the Terrible, Alexandr Nevsky (directed by Sergei Eisenstein), The Generation of Winners, The Circus (directed by Grigorii Alexandrov), and others.

Перевод

Надежда Ламанова занимает особое место среди дизайнеров одежды 1920-х годов не только потому, что она была первым профессиональным дизайнером одежды своего времени, но и из-за огромного вклада, который она внесла в развитие теоретических принципов советского дизайна, и создания первых примеров современной одежды.

Ее профессиональная жизнь началась в 1885 году, когда в возрасте 24 лет она открыла собственную мастерскую. Ее талант вскоре стал известен, и когда она открыла в Москве свое дело, то пользовалась большой популярностью и широкой клиентурой среди интеллигенции, писателей, актеров и художников. То, что привлекало всех, было не только исключительным талантом Ламановой и ее профессиональным мастерством, но и подлинной художественной достоверностью. Ее острый глаз, тонкий вкус и глубокое знание костюма помогли ей сразу же разобраться в особенностях характера и фигуры человека и безошибочно выбрать самый подходящий покров и стиль платья.

Ежегодные поездки в Париж, центр моды того времени, усовершенствовали ее знания. Она сотрудничала с самым знаменитым дизайнером Франции, Полем Пуаре, который мгновенно распознал необыкновенный талант русской художницы и неоднократно просил ее переехать в Париж, чтобы работать с ним. Однако Ламанова отказалась.

Автобиография Ламановой в разделе «Творческие биографии».

Накануне Октябрьской революции, когда Ламановой было 46 лет, ее фирма утверждала, что ее клиентами являются самые высокие аристократические круги, а надпись на вывеске гласила - «Поставщик Двора Его Императорского Величества».

Возможно, некоторые художники, заслужившие официальное и общественное признание и твердую позицию в обществе, в свои преклонные годы не пережили духовных потрясений революции и ее вторжения в свою художественную жизнь. Однако Ламанова без колебаний приняла революцию и одобрила ее идеалы. Она объяснила свою позицию:

«Революция изменила мое имущественное положение, но она не изменила моих жизненных идей, а дала возможность в несравненно более широких масштабах проводить их в жизнь». (Записки Н. Ламановой. Рукопись. Архивы Т. Стриженова.)

Ее позиция объясняется ее биографией. Надежда Ламанова была ребенком обедневшего военнослужащего, стала сиротой, будучи еще молодой, и ей пришлось содержать свою младшую сестру, сочетая работу с учебой. В годы Первой мировой войны, когда Ламанова уверенно стояла на ногах, она с готовностью разрешила использовать свое имение в качестве военного госпиталя.

Ее главными характеристиками были доброта, гуманизм и простота. Она рассталась со своей фирмой и привилегиями своего положения без жалоб. Она также испытала много трудностей в жизни: в первые годы после революции она провела в Бутырской тюрьме с обвинением в «буржуазии», была освобождена через заступничество писателя Максима Горького, тогдашнего главы государственного издательства. В 1930-е годы она была лишена избирательных прав, и ей и ее друзьям пришлось неустанно возражать, чтобы доказать, сколько она сделала для советской системы.

Никакое унижение, казалось, не подавило волю этой замечательной женщины.

Творческая биография Ламановой также очень сложна. До революции она работала в модном стиле модерн, ее работы следуют тенденциям Парижской одежды. Несколько таких платьев находятся в ленинградском Эрмитаже. Предназначенные для российской аристократии, они характеризуются сложным и трудоемким исполнением, а также использованием дорогих зарубежных тканей и украшений. Хотя они отличаются друг от друга в разрезе, форме и декоративных деталях, они схожи элегантностью силуэта, идеальной пропорцией и умным выбором текстуры и цвета - одним словом, они обладают гармонией, которая отличает произведение искусства от обычного пошива одежды.

Дар Надежды Ламановой схож с талантом скульптора - она могла представить себе, как каждая ткань будет выглядеть на человеке и какая фигура подходит фигуре. Она сама не делала одежды, а делала «закрепление» материала на человеческой фигуре, очерчивая контуры разреза и украшения. Ее метод дизайна одежды можно назвать «скульптурой в ткани».

Ламанова часто рассказывала своим ученикам, что самым важным аспектом их работы было найти форму костюма, подходящего для человека, а не изобретать «стиль» или модные атрибуты, которые якобы определяют эстетические достоинства одежды. Она считала, что костюм неотделим от человека. Поэтому художница изгнала слова «стиль» и «мода» из словаря дизайнеров, заменив их понятиями «форма» и «дизайн». Она была первой, кто провел линию между задачами дизайнера костюмов и швеей, подчеркивая их специфику:

«Я работаю в деле пошивки женского платья как художник, то есть я создаю новые формы, новые образцы женской одежды… Я должна пояснить, что я лично создаю модели и образы женской одежды, их накалываю и оформляю, но не провожу сама техническую сторону работы. Я не могу проводить эту работу, как архитектор не может сам строить дом, а кузнец не может работать один без молотобойца…» (Заметки Н. Ламановой. Рукопись. Архивы Т. Стриженова.)

Ламанова не делала зарисовки своих эскизов, потому что не могла рисовать; они известны на фотографиях реальных моделей, размещенных в ее личных архивах. (Эти архивы были любезно предоставлены мне младшей сестрой художницы Марией Петровной и ее племянницей Надеждой Крахт. Воспоминания о ее родственниках, учениках и знакомых, почти все из которых теперь мертвы, также важны для понимания искусства Ламановой. Помогли в подготовке этой книги ныне покойные Ф. Гореленкова и Н. Макарова, две ученицы Надежды Ламановой).

В то время как в личной жизни Надежда Ламанова была исключительно любезна, в своей работе она была серьезна и требовательна, полностью уверена, что ее точка зрения верна. Она редко принимала во внимание пожелания клиентов и была тверда в выборе дизайна. Для нее был по-настоящему творческий акт: она размышляла над стилем и системой кройки, рассматривая распределение складок текстиля на фигуре, имея в виду все особенности конструкции по отношению к форме тела. Более того, она обратила внимание не только на линии «фронта», но и на фигуру как пластику объема, всегда проверяя, как изменилось платье при его движении.

Как вспоминают актеры, знавшие Надежду Ламанову, с ней было трудно и легко работать. Это было сложно из-за того, как она твердо принимала решение о стиле костюма, без учета их пожеланий. Примерки у нее были долгими и неоднократными, она выматывала и не отпускала клиента, пока не была уверена, что все идеально. С другой стороны, это было легко, потому что она была абсолютно надежна: результатом работы всегда было безупречно выполненное платье.

С революцией в жизни Ламановой началась новая эра: ее талант и огромный практический опыт позволили ей наконец заняться крупными и разнообразными видами деятельности. Взяв на себя инициативу по реструктуризации одежды, художница испытала в свои последние годы омоложение своих творческих способностей.

Она с энтузиазмом присоединилась к работе советских учреждений, демонстрируя выдающиеся организационные способности. Она создала Мастерские современного костюма при отделе художественной промышленности Наркомпроса, стала членом отдела одежды Государственной Академии Художественных Наук и сотрудничала с журналами «Ателье» и «Красная нива», выступая как автором статей, так и дизайнером одежды. Концепция цели искусства, выраженная в романтических революционных лозунгах этих неспокойных дней, и стремление интегрировать искусство во все аспекты повседневной жизни и промышленности нашло отклик в творческих идеях дизайнера.

Несмотря на трудоемкую административную и организационную работу, она продолжала разрабатывать одежду. Она писала в 1922 году: «Работа моя заключается в создании моделей современной женской одежды, причем я всегда стремилась проводить в своих моделях простоту и логичность, исходя в этих исканиях главным образом от материала…» (ЦГАЛИ, Фонд 941, опись 10, ед. хр. 341, с. 3)

В годы после революции у Ламановой была четкая концепция тенденций в советском костюме: одежда для повседневной одежды и одежды с фольклорными мотивами. В качестве модели Ламанова чаще всего использовала Александру Хохлову, актрису немого кино, ее ученицу Надежду Макарову и Лилю Брик. Иногда к любительским фотографиям подклеены кусочки ткани, из которых изготовлена одежда. Они простые, плохо окрашенные и, как правило, не узорчатые ткани: небеленое суровое полотно, фланелет и ситец. С ними художница выпускала простые платья с удлиненными пропорциями, в основном сорочечного типа. Для украшения иногда использовались декоративные цветные вставки или чередующиеся темные полосы на белом фоне, которые несколько напоминали геометрические рисунки конструктивистов; часто тонкий рисунок ткани был основой украшения платья.

Чувствуется, что Ламанова сознательно и принципиально пыталась упростить крой. В ее пояснительной записке к проекту мастерской современного костюма художница отмечала, что новые мастерские могут разработать «методы упрощения костюма как характерный признак костюма трудящегося в его противоположности костюму буржуазии» (личный архив Н. Ламановой). Но это был не единственный ее мотив для упрощения.

Неприхотливая одежда, безусловно, соответствовала суровой жизни того времени. Нужны были вещи, которые были простыми, удобными, недорогими и практичными. Доступные материалы - хромовые ткани, которые не могли сохранить форму, или, с другой стороны, толстый, грубый материал (в основном солдатская ткань) - продиктовали форму, которая подойдет предмету одежды. Неудивительно, что основная формула Ламановой заключалась в следующем: «Материал определяет форму».

Любительские фотографии в ее архивах позволяют нам следить за течением ее художественного поиска. Например, можно увидеть три модели пальто, очень похожие в разрезе: у них есть общий силуэт, стоячий воротник и широкий пояс.

Но каждая модель имеет свое решение, в зависимости от ее назначения. В коротком пальто из шерстяной ткани подчеркнута обтекаемость формы, особая скульптурная четкость членений, выявленная строчкой рельефность линии борта. Кроме того, это модель того же пальто из холста, более тонкий материал: у него есть подкладка под стоячим воротником, создающие живописную игру с жесткими маленькими складками; ремень застегивается с пряжкой, обернутой струной; он расположен ниже, в середине, прямоугольный вырез, который придает оригинальность предмету одежды и выполняет определенные функции, предотвращающие складки при ходьбе. В третьей версии пальто (вероятно, сделанного из фланелета) пропорции изменены: он длиннее и значительно шире, чем первые два, поэтому ткань падает в мягкие складки. Талия плотно завязана широким поясом.

Таким образом, Ламанова продемонстрировала возможности формирования нескольких вариантов из одной конструкции.

В архивах Ламановой есть один акварельный эскиз, на котором изображена необычная модель - платье в разных тонах синего. Он не подписан, но, судя по тонкой цветовой гамме и уверенному и свободному удару кисти, исполнителем могла быть подруга Ламанова Александра Экстер. Это платье тоже скроено как сорочка, с высокой шеей, довольно широкими рукавами и широким дважды намотанным кушаком из того же материала, что и декоративная черная пряжка в выпуклом прямоугольнике. Поверх платья носится короткая куртка с короткими рукавами, короче и шире, чем у платья.

Эта обманчиво простая модель — шедевр. Такая деталь образует вторую версию костюма. Скромные, изысканные декоративные детали включают полоски серого, терракотового и синего цвета, украшающие воротник, манжеты и створки.

Предполагается, что модель должна быть изготовлена из ткани, такой как крепкий атлас, благодаря чему будет выглядеть «нарядным» платьем.

Однако, скорее всего, эта одежда никогда не производилась. Ламанова также разработала большую серию повседневных платьев, выполненных из одной формы, вытянутого прямоугольника. Эти простые предметы одежды приобретали индивидуальность из-за декоративной аппликации в виде сломанных геометрических линий или тонких полукругов.

Ламанова проявила гораздо большую свободу при разработке платьев с изображением народных мотивов. Ее обращение с этими мотивами было совершенно неожиданным и всегда удивительным. Она использовала куски неподдельного антикварного кружева для нижней части платья с современной обрезкой зубчатого края (пикота), используя подлинное русское полотенце для передней части платья и делала лифы из кружевных занавесок, богато вышитых сатинировкой. Это была не просто «аппликация», как во многих таких произведениях народного творчества, а конструкция интегральной конструкции как пластикового объема, координация всех ее элементов.

Эта сторона работы Ламановой была довольно осознанной: она прекрасно понимала, что обратилась к портнихам любительницам, которые, используя свои методы, могли улучшить свою одежду и индивидуализировать их с помощью вышитых полотенцами, наволочками, вязанием крючком и другими традиционными домашними элементами.

Предметы одежды в этом жанре художница отправила на экспозицию международных выставок декораций и индустрии моды, состоявшуюся в Париже в 1925 году. Прямоугольное платье включало богато вышитое полотенце. В нижней части; аналогичные полотенца использовались для сторон и спины. Узкая красная коса обрезала вырез и рукава, гармонизируя все. Для соответствия была небольшая маленькая шляпа. Этот ансамбль, простой, но сенсационный, вызвал большой переполох среди изысканной общественности Парижа. Ламанова получила Гран При «за национальную самобытность в сочетании с современным модным трендом». В своей статье «Русский стиль», Ламанова писала: «Одним из интересных заданий в области современного костюма является разработка и применение форм и характера народного костюма к костюму нашей повседневной жизни. Целесообразность народного костюма, благодаря вековому коллективному творчеству народа, может служить как идеологическим, так и пластическим материалом, вложенным в нашу одежду города. Основные формы народного костюма всегда мудры… Именно, взяв известную красочность и разместив ее в ритмической последовательности на целесообразно сделанном костюме, мы получаем тот тип одежды, который и является отвечающим нашей современной жизни». (Красная нива, 1923, № 30, с.32). Хотя статья не является подписанной, большинство людей согласны с тем, что это, скорее всего, было написано Ламановой. Более того, образец одежды, иллюстрирующий его, очень напоминает скаты, найденные в личных архивах художницы, и ее статью «О современном костюме», опубликованную в журнале «Красная Нива» (1924, № 27, стр. 662-663)). Таким образом, Ламанова продемонстрировала возможности формирования нескольких вариантов из одной конструкции.

Иногда дизайнер включала, казалось бы, несогласованные элементы: например, в модном «мантелет-платье» она использовала фрагмент народной вышивки, полоски разного цвета вдоль подол и манжеты и длинный ряд больших кнопок, асимметрично расположенных вдоль боковой стороны.

Необычный мантелет начался с рукавов и стал частью платка, висевшего в треугольнике по спине. Мантелет можно было носить поверх повседневного платья, превращая его в оригинальный, модный ансамбль.

Любимым видом одежды художницы был женский костюм, состоящий из платья, юбки и куртки, которую она назвала «кафтан». Эти ансамбли могли бы подчеркнуть качество ткани (когда она была хорошего качества) и, что одинаково важно, позволяют дизайнеру сравнивать и контрастировать детали: узкую прямую юбку с блузкой, подходящую для йоги, прямое длинное платье с пышными рукавами; иногда платье украшено асимметрично расположенными складками.

Ламанова считала, что контраст в дизайне моделей делает их динамичными: «Отсутствие контраста и, следовательно, динамизма делает силуэт сухим, монотонным и безжизненным». Теория и практика Ламановой близко напоминали конструктивизм в их функционализме и целесообразности. Однако в работах художницы преобладает эмоциональный принцип. Орнамент и цвет были его проводником. Теория Ламановой по законам орнамента одежды также очень интересна, хотя и не имеет прямого отношения к дизайну для массового производства. В своих лучших произведениях художница проявляла чувство пропорции в характере и размещении штрихов одежды, украшения. Непечатаемые ткани и прямые силуэты типа раковины оставляли большие гладкие поверхности, требующие украшения. Следуя народным принципам орнамента, Ламанова распределяла декоративные элементы в местах, продиктованных конструкцией одежды, таких как лиф, плечи, манжеты и подола.

Чаще всего она использовала подлинные народные мотивы - границы салфеток или полотенец - но иногда она сама делала орнамент в конструктивистском или современном стиле. Особенности и ритм украшения гармонизированы с общим контуром, конкретным разрезом, текстурой и цветом ткани. Орнамент в повседневном костюме стал заботой Ламановой после 1924 года, когда она стала главой мастерской декоративно-прикладного искусства, которая выполняла заказы на «Кустэкспорт» («Ремесленный экспорт») и другие организации для отечественных и международных выставок. Дизайнер стал уделять больше внимания этничности в костюмах и украшениях. Увлеченная декоративным блеском вышивки, она иногда использовала ее в избытке, и эти конструкции казались менее интегрированными, чем ее более сдержанные модели.

Из ее архивов легко видеть, что все работы Надежды Ламановой, какими бы разнообразными они ни казались, имеют общий «единый фундамент», прямоугольник. Принимая во внимание свойства и возможности тканей, которые были доступны, художница «перевела» прямоугольник в бесчисленные одежды. Отправной точкой для большинства портных была мода; они игнорировали свойства материала и даже пытались скрыть их сложным декоративным дизайном. Ни индивидуальные характеристики, ни даже фигура владельца не имели большого отношения к дизайну. Неудивительно, что мода на корсет длилась так долго (в Европе он все еще носился в 1920-х годах). Эта искусственная рамка изменяла и часто искажала фигуру, подчиняя ее конструкции платья.

Проекты Ламановой не увенчались успехом, и она была вынуждена оставаться в рамках лабораторных экспериментов.

Разочарованная отсутствием промышленных возможностей для обеспечения населения приличной современной одеждой, Ламанова попыталась привлечь еще одну категорию населения. С ее ближайшей подругой Верой Мухиной она опубликовала в 1925 году альбом «Искусство в быту», в котором они обратились к женщинам, которые делали свои собственные платья, предлагая им свои образцы повседневной одежды, которые были просты в крое и понятны начинающим. Каждый рисунок модели сопровождался чертежом кроя и подробным описанием соответствующих тканей и даже цветовыми предложениями. Геометризируя свои рисунки, авторы упростили свои шаблоны до крайности, подписываясь на принципы известных конструктивистов, разделивших все рисунки на геометрические плоскости. Редакция в альбоме заявила, что состояние страны в то время «не дает достаточных материальных предпосылок для радикальной трансформации всей нашей культуры, которая придет с окончательным триумфом социализма... Новые формы, культура одевания, рациональная и хорошо организованная повседневная жизнь, может быть достигнута без помощи профессионалов, но с творческими усилиями рабочей семьи, школьного или клубного коллектива» («Искусство в быту», Москва, 1925).

Ламанова постоянно продумывала предназначение дизайна - для промышленности или для небольшой мастерской - о возможности использования ее моделей дома. Ее модели поощряли портних любительниц искать простые, целесообразные формы и научили их разумному использованию народных тем.

В альбоме были представлены летние и зимние платья, куртки и пальто, спортивная одежда и униформа «Молодой пионер». Были даже театральные костюмы Владимира Ахметьева, в том числе костюм женщины-работницы, которую можно было легко трансформировать в костюм «буржуа». И вырезанные, и декоративные элементы рисунков подчеркивали их отличительный национальный характер. Одним из самых интересных образцов было платье из платочков. Кашемировая ткань и маленькие красные и зеленые цветы, напечатанные на платочках, придавали костюму натурализма модный призыв. Также привлекательным был костюм в трех вариантах: носить на улице, дома и на работе. Его преобразования зависели от минимальных изменений. Прямое, внушительно выглядещее пальто было вырезано, с предельной простотой, из армейской ткани. Оно описано в альбоме: «Пальто (ширина ткани около двух метров) имеет один кусок. Вырезается только пройма. Втулка имеет только один шов: выступающая деталь в узоре, когда она складывается в два, образует ластовицу для свободного перемещения руки. Воротник представляет собой половину квадрата; его длинная диагональная сторона сшита под шее после пунктирной линии. После сшивания оставшиеся концы воротника застегиваются на плечевой линии. Если ткань у́же, стороны имеют швы с формой оставшегося прямоугольника» («Искусство в быту», Москва, 1925 г. (из описания модели)). В одежде альбома есть своего рода прозодежда: рубашка в стиле Толстого, блузка и юбка (дизайнер В. Ахметьев); спортивный костюм, состоящий из блузки и кулотов; и головной убор (дизайнер В. Мухина). Альбом также содержит легко реализуемые строительные проекты: деревенская библиотека и читальный зал, деревенский театр, книжный шкаф в сочетании с витриной и многое другое. Художники из разных областей старались помочь с минимальными ресурсами создать новую среду, соответствующую новой жизни. Дизайн альбома, сделанный Верой Мухиной, был хорошо продуман и великолепно выполнен до мельчайших деталей.

Сочетание оригинальных рисунков и планов, красивая типография и умелое использование цвета сделали объем ярким примером изобразительного искусства в дизайне. Ламанова работала над дизайном повседневных костюмов примерно до середины 1920-х годов, и некоторое время после этого занималась дизайном моделей из домотканого текстиля. Ее вклад в теорию дизайна одежды был существенным. Она написала программу для мастерских современного платья и учебных планов первых советских школ по дизайну одежды, сделала доклады на конференциях и написала ряд статей для журнала «Красная нива». Похоже, что художница готовилась издавать книгу, суммируя ее обширный опыт. Она написала в 1922 году в своей автобиографии: «Я приступила к теоретической обработке тех данных, которые были мною выработаны за мою деятельность» (ЦГАЛИ, Фонд 941, опись 10, дело 341. Автобиография Н. Ламанова).

Даже если Ламанова не могла рисовать, у нее точно был литературный дар. Ее многочисленные статьи впечатляют не только их великолепным мастерством сложных задач костюма, но и их логикой и композиционной гармонией фраз. В своей статье «Русский стиль» Ламанова подняла вопрос о новом советском костюме и традициях. (Красная нива, 1923, № 30, с.32). В ее знаменитой статье «О современном костюме» (Красная нива, 1924, № 27, стр.662-663) содержится классификация новых форм одежды в повседневной и праздничной одежде, показано их родство с принципами народного костюма, подробно анализируется необходимость создания костюма в соответствии с индивидуальным образом.

В работах Ламановой есть еще одна статья, подготовленная для печати «О рациональности костюма». По-видимому, это послужило основой для теоретической программы 1928 года. Именно здесь художница сформулировала формулу «основной идеи костюма» и «цель, ради которой создается костюм, для кого и для чего», которую она прославила как кредо дизайнеров одежды.

Теория Ламановой была обнародована в полном объеме в 1928 году и была представлена на выставке «Кустарная ткань и вышивка в современной женской одежде». Основными пунктами программы были цель костюма, его материал, фигура владельца и его форма:

Цель костюма определяет материал.

Материал определяет форму.

Фигура, в свою очередь, определяет материал и цвет.

Форма определяет материал, орнамент и ритм, который координирует эти элементы.

Орнамент используется для интеграции материала и цвета.

Орнамент используется для построения формы и веса.

Орнамент делит плоскость как художественно, так и конструктивно.

Форма прямоугольника определяется материалом.

Материал следует использовать экономно, с небольшим количеством отходов при кройке.

Форма должна допускать свободное перемещение. (Т. Арманд, Орнаментация ткани, Москва, Ленинград, Академия, 1931, с.103).

Эти краткие тезисы, которые сегодня могут казаться само собой разумеющимися, вызвали революцию в искусстве платья. Они создали основу для обширной отрасли декоративного искусства, которая соответствовала природе новой жизни и была также ее продуктом. Принципы теории Ламановой все еще могут применяться сегодня не только в дизайне костюмов, но и в других декоративных искусствах.

Еще одной важной сферой деятельности замечательной художницы была ее работа для театра и кино. Ламанова работала в Московском художественном театре в течение сорока лет, с 1901 по 1941 год, год ее смерти. Она создала множество костюмов, для иностранных классиков, а также для пьес советских авторов. Талант художницы в этой области был описан Станиславским в его письме к Александру Головину, дизайнеру декораций и костюмов для спектакля 1926 года в комедии Бомарше «Женитьба Фигаро»: «Мы делали пробы шитья черновых костюмов обычными портными и портнихами. Эта проба выяснила с большой очевидностью, что эти люди аромата Вашего таланта передать не смогут. Нам ничего не оставалось делать, как обратиться к тому лицу, которое мы считаем в Москве единственно художественно чутким для работы с Вашими эскизами. Этим человеком оказалась Ламанова. Вероятно, Вы думаете, что она обычная портниха, которая каждому современному костюму придает модный фасон. Ламанова большая художница, которая увидав Ваши эскизы, вспыхнула настоящим артистическим горением. Она для каждого костюма собственными руками будет искать не шаблонных и модных, а индивидуальных приемов шитья». (К. Станиславский.« Собрание сочинений », т. 8, Москва, Издательство« Искусство », 1961, стр. 136-137)

В 1920-е годы Надежда Ламанова также служила для театров имени Евгения Вахтангова, Театра революции и Театра Красной Армии. В своей работе для кино она сделала костюмы для фильмов «Аэлита» (режиссер Яков Протазанов), «Иван Грозный», «Александр Невский» (режиссер Сергей Эйзенштейн), «Поколение победителей», «Цирк» (режиссер Григорий Александров) и другие.

Использованные источники:

🕮 Strizenova Tatiana "Soviet Costume and Textiles 1917-1945" Published by Flammarion, 1991

🕮 Стриженова Т.К. «Из истории советского костюма» Учебное издание. – М.: Советский художник, 1972.